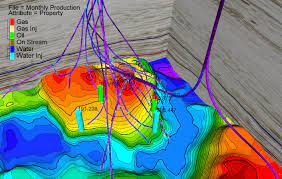

Syntillica offers Petroleum Engineering to provide field review, production forecasting and optimization for the best ways to produce a field.

Petroleum Engineering covers a range of subject areas such as field appraisal to understand how a field has been produced historically and what can be done to extend field lifetime and to sustain or improve declining production. By studying production on a field, and incorporating reservoir knowledge, future production can be predicted along with the options such as pumps, injection, artificial lift, workovers, completions and input to well plans to get the most from the reservoirs.

Syntillica can provide the expertise to cover the full range of Petroleum Engineering subjects from desktop studies, well planning and through to field review and development planning.

Technically recoverable volumes refer to the quantity of hydrocarbons (oil and natural gas) in a reservoir that can be extracted using current technology and operational practices, without considering the economic viability. This concept is crucial for understanding the potential of a reservoir, guiding exploration, development planning, and resource management.

Key Concepts of Technically Recoverable Volumes

Conclusion

Technically recoverable volumes are a critical measure in petroleum engineering, representing the potential hydrocarbons that can be extracted with current technology. Understanding these volumes allows engineers, geologists, and decision-makers to assess the potential of reservoirs, plan field development, and make informed decisions about investments and operations. As technology advances and new techniques are developed, the technically recoverable volumes of a reservoir may increase, underscoring the importance of continuous evaluation and adaptation in the field of petroleum engineering.

Water injection is a widely used technique to enhance oil recovery and maintain reservoir pressure. This method involves injecting water into an oil reservoir to displace hydrocarbons towards production wells, thereby increasing the amount of recoverable oil. It is one of the most common secondary recovery techniques used in the industry.

Key Concepts of Water Injection

Conclusion

Water injection is a fundamental technique in petroleum engineering that plays a critical role in enhancing oil recovery and maintaining reservoir pressure. By displacing oil towards production wells, it enables more hydrocarbons to be extracted from a reservoir than would be possible through primary recovery alone. Effective water injection requires careful planning, monitoring, and management to address technical challenges and maximize the economic benefits while minimizing environmental impacts. As a widely used and cost-effective method, water injection remains a key tool in the field of petroleum engineering.

Well planning is the comprehensive process of designing and preparing for the drilling of oil or gas wells. It involves the integration of geological, engineering, and economic considerations to ensure that the well is drilled safely, efficiently, and economically while achieving the desired production objectives. Effective well planning is crucial for the success of any drilling project, whether it’s an exploration, appraisal, or development well.

Key Components of Well Planning

Conclusion

Well planning in petroleum engineering is a multidisciplinary process that integrates geological, engineering, economic, and environmental considerations to design and execute successful drilling operations. Effective well planning minimizes risks, controls costs, and maximizes the chances of achieving the desired production outcomes. By carefully considering each aspect of the well, from initial geological analysis to post-drilling evaluation, petroleum engineers can ensure that wells are drilled safely, efficiently, and economically, contributing to the overall success of oil and gas projects.

Artificial lift refers to the various methods used to increase the flow of liquids (typically oil and water) from a production well when natural reservoir pressure is insufficient to push the fluids to the surface. As oil and gas reservoirs mature, the natural drive decreases, and artificial lift methods become necessary to maintain or enhance production rates.

Key Concepts of Artificial Lift

Conclusion

Artificial lift is a critical component of petroleum engineering that allows for the continued and enhanced production of oil and gas from wells with insufficient natural reservoir pressure. The selection of the appropriate artificial lift method depends on various factors, including well depth, production rate, fluid properties, and economic considerations. Advances in technology, particularly in automation and materials science, continue to improve the efficiency and reliability of artificial lift systems, making them an indispensable tool in the modern petroleum industry. By carefully selecting and managing artificial lift systems, operators can optimize production, extend the life of wells, and maximize economic returns while ensuring environmental responsibility.

Key Concepts of Production Forecasting

Conclusion

Production forecasting is a vital component of petroleum engineering, providing the basis for field development, economic evaluation, and reservoir management decisions. It involves a range of methods, from empirical decline curve analysis to sophisticated reservoir simulations, each with its strengths and limitations. The accuracy of production forecasts depends on the quality of data, the complexity of the reservoir, and the assumptions made in the models. Advances in technology, particularly in machine learning and real-time data integration, are improving the reliability and responsiveness of production forecasts, helping to optimize hydrocarbon recovery while managing economic and environmental risks.

Polymer surfactants are an advanced technology in petroleum engineering, primarily used in Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) processes. They combine the properties of polymers and surfactants to improve oil recovery from reservoirs where traditional methods have become less effective. Polymer surfactants enhance the mobilization and displacement of oil trapped in porous rock formations by reducing the interfacial tension between oil and water and modifying the rheological properties of the injected fluids.

Key Concepts of Polymer Surfactants

Conclusion

Polymer surfactants represent a powerful tool in the arsenal of petroleum engineers, particularly in the context of Enhanced Oil Recovery. By combining the properties of polymers and surfactants, these compounds can improve the displacement efficiency of water flooding, reduce residual oil saturation, and ultimately increase the amount of oil recoverable from a reservoir. Despite challenges related to degradation, adsorption, and environmental impact, ongoing research and technological advances are expanding the potential of polymer surfactants, making them a viable option for increasing oil recovery in complex and mature reservoirs.

Gas injection is a widely used method for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR). It involves the injection of gas into an oil reservoir to increase pressure, reduce oil viscosity, and improve oil displacement towards production wells. Gas injection can be implemented in different forms, including miscible and immiscible gas injection, depending on the interaction between the injected gas and the reservoir fluids.

Key Concepts of Gas Injection

Conclusion

Gas injection is a critical method in petroleum engineering for enhancing oil recovery, particularly in reservoirs where conventional methods have reached their limits. By injecting gases such as CO2, nitrogen, or natural gas, engineers can maintain reservoir pressure, reduce oil viscosity, and improve oil displacement, leading to increased recovery rates. The effectiveness of gas injection depends on careful planning, reservoir suitability, and continuous monitoring. Despite challenges such as gas breakthrough and reservoir heterogeneity, ongoing advancements in technology and methods are making gas injection a more viable and efficient EOR technique. Additionally, the use of CO2 for gas injection also presents an opportunity for carbon sequestration, contributing to more sustainable oil production practices.

Key Concepts of Economic Asset and Reserves Estimation

Conclusion

Economic asset and reserves estimation in petroleum engineering is a complex process that combines technical expertise with economic analysis to determine the value and viability of oil and gas projects. Accurate reserves estimation methods, such as volumetric analysis, decline curve analysis, and reservoir simulation, are essential for determining the quantity of recoverable hydrocarbons. Economic valuation techniques, including cash flow analysis, cost estimation, and risk assessment, are used to assess the profitability and risk associated with petroleum assets.

The integration of technical and economic data, along with adherence to industry standards like SPE-PRMS and SEC rules, ensures that reserves and asset valuations are reliable and transparent. Despite challenges related to data uncertainty, price volatility, and regulatory changes, advancements in digital technologies and EOR techniques are enhancing the precision and effectiveness of asset and reserves estimation in the petroleum industry.